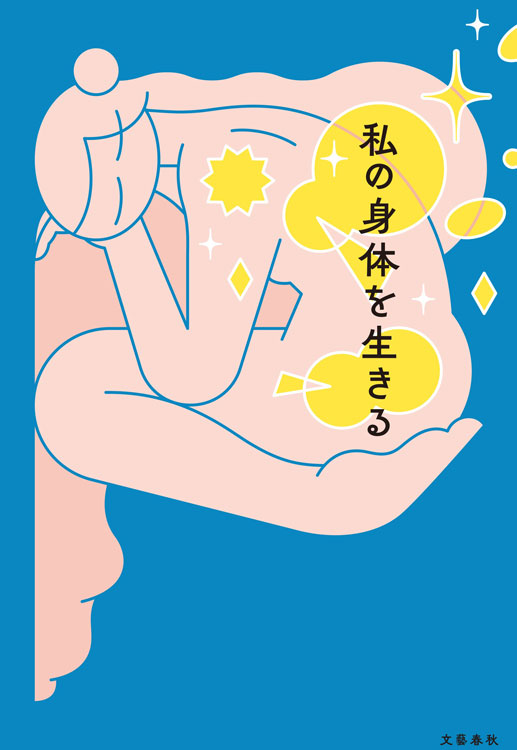

[273rd] Michiko Mamuro's Bookshelf "Living My Body" Bungeishunju

Known as the "original charismatic bookseller," DAIKANYAMA TSUTAYA BOOKS, who recommends books in a variety of media including magazines and TV.

In this series, we take a peek into the "bookshelves" in the mind of our most popular concierge.

Please enjoy it along with his comments.

* * * * * * * *

"Living in my body"

Kanako Nishi, Sayaka Murata, Hitomi Kanehara, Rio Shimamoto, Kaori Fujino, Suzumi Suzuki, Akane Chihaya, Mariko Asabuki, Ellie, Mineko Nomachi, Kotomine Lee, Hiroka Yamashita, Akane Torikai, Yuka Shibasaki, Rin Usami, Marina Fujiwara, Ameko Kodama / Bungeishunju

Click on the image to go to the purchase page.

Click on the image to go to the purchase page.

* * * * * * * *

The other day, some male comedians were talking about child-rearing on TV. They became fathers in their early 40s and are now in their mid-40s, with children aged 2-3. The child is estimated to weigh 12-13 kg. They couldn't hold the baby for long and put it down immediately. One of them was dejected and said, "As a man, I feel depressed."

But I thought that a woman in the same situation wouldn't say she was "depressed as a female." If she were to say something, it would be "depressed as a mother."

Both online and in real life, I see and hear women raising children say that they feel "shameful as a mother" when they can't hold their baby for long, when their breast milk doesn't come in, or when their baby won't stop crying.

But that doesn't mean that men have it easy. When they are inferior to other dads in terms of strength, leg strength, or stamina, their wives, perhaps unconsciously, and their babies, who are only a few months old, may look at them with indescribable looks... and they often hang their heads. In my opinion, even now in the year 2024, men in our country live their lives weighing "strength" and women "love."

Now, this book is a collection of essays by women/writers living as women who confront the body. The essays are all up-and-coming, and there is not a single piece of writing that is structured around "motherhood" or "love." There is no "female" either. (Only once in Rin Usami's book does a female "weasel" appear, not a human.)

When I read this kind of book, I run the "man" through my mind, because I feel like it deepens the story.

Tomoka Shibasaki wrote that after receiving the request to write the essay, she met with the editor to talk about it in person. "What I wanted to confirm was why they were limiting the gender of the writers," she wrote. "Women have long been oppressed from speaking about their bodies and sexuality in their own words, but at the same time, it is women and sexual minorities who are asked to explain and give reasons for their bodies and sexuality," which got me thinking.

Certainly, there are many books written by women and sexual minorities. But on the other hand, I can't think of any books written by male authors who are not oppressed, but who talk about the body or sexuality in their own words. In my experience, when I read about men's "my body and sexuality," I have only read things that are like a model or aspirations for "how a male should be." The world of manga, not print, is where there is an abundance of such books.

Manga is full of works in which boys and young men vividly confront life and the flesh, such as: disgusted with their own sexuality, having unspeakable fantasies every night about a popular girl in class, thinking they might be crazy, being seen in an inappropriate scene by a girl, wanting to chop off their genitals.

Leaving the topic aside, Suzuki Suzumi writes about the first time she was molested on a train. She was in her second year of junior high school at the time, and writes, "At least I didn't feel like something important to me had been hurt," and adds, "I couldn't calm down, feeling a vague sense of guilt, like when I carelessly break something important to my mother. Looking back, at this point in time, my body may have still belonged to my mother more than it did to me."

There may be many women who think they were like that in their mid-teens, and some who think they didn't feel that way but understand why Suzuki felt that way. But there is probably no 14-year-old boy who thinks that "my body belongs to my mother." And there is probably no boy who thinks that "my body belongs to my father." When were boys able to decide that their body belongs to them?

Others include Shimamoto Rio, who writes, "The subject of my appearance has always been someone other than myself," and Ellie, who looks at the baby as "new eyes, claws, organs and voice that are derived from my body along with the sperm."

And it was Mineko Nomachi who blew to pieces the pretentiousness and self-satisfaction of "reading this kind of thing while running alongside a man" that I mentioned earlier. Every time I read a few lines, I had to stop, pant, and take a deep breath. The line "I am not a material for diversity" breaks my heart no matter how many times I read it. I am overwhelmed by her complete lack of understanding.

This book was written by seventeen people who tore themselves apart. We call for the publication of writers who live as men/men.

But I thought that a woman in the same situation wouldn't say she was "depressed as a female." If she were to say something, it would be "depressed as a mother."

Both online and in real life, I see and hear women raising children say that they feel "shameful as a mother" when they can't hold their baby for long, when their breast milk doesn't come in, or when their baby won't stop crying.

But that doesn't mean that men have it easy. When they are inferior to other dads in terms of strength, leg strength, or stamina, their wives, perhaps unconsciously, and their babies, who are only a few months old, may look at them with indescribable looks... and they often hang their heads. In my opinion, even now in the year 2024, men in our country live their lives weighing "strength" and women "love."

Now, this book is a collection of essays by women/writers living as women who confront the body. The essays are all up-and-coming, and there is not a single piece of writing that is structured around "motherhood" or "love." There is no "female" either. (Only once in Rin Usami's book does a female "weasel" appear, not a human.)

When I read this kind of book, I run the "man" through my mind, because I feel like it deepens the story.

Tomoka Shibasaki wrote that after receiving the request to write the essay, she met with the editor to talk about it in person. "What I wanted to confirm was why they were limiting the gender of the writers," she wrote. "Women have long been oppressed from speaking about their bodies and sexuality in their own words, but at the same time, it is women and sexual minorities who are asked to explain and give reasons for their bodies and sexuality," which got me thinking.

Certainly, there are many books written by women and sexual minorities. But on the other hand, I can't think of any books written by male authors who are not oppressed, but who talk about the body or sexuality in their own words. In my experience, when I read about men's "my body and sexuality," I have only read things that are like a model or aspirations for "how a male should be." The world of manga, not print, is where there is an abundance of such books.

Manga is full of works in which boys and young men vividly confront life and the flesh, such as: disgusted with their own sexuality, having unspeakable fantasies every night about a popular girl in class, thinking they might be crazy, being seen in an inappropriate scene by a girl, wanting to chop off their genitals.

Leaving the topic aside, Suzuki Suzumi writes about the first time she was molested on a train. She was in her second year of junior high school at the time, and writes, "At least I didn't feel like something important to me had been hurt," and adds, "I couldn't calm down, feeling a vague sense of guilt, like when I carelessly break something important to my mother. Looking back, at this point in time, my body may have still belonged to my mother more than it did to me."

There may be many women who think they were like that in their mid-teens, and some who think they didn't feel that way but understand why Suzuki felt that way. But there is probably no 14-year-old boy who thinks that "my body belongs to my mother." And there is probably no boy who thinks that "my body belongs to my father." When were boys able to decide that their body belongs to them?

Others include Shimamoto Rio, who writes, "The subject of my appearance has always been someone other than myself," and Ellie, who looks at the baby as "new eyes, claws, organs and voice that are derived from my body along with the sperm."

And it was Mineko Nomachi who blew to pieces the pretentiousness and self-satisfaction of "reading this kind of thing while running alongside a man" that I mentioned earlier. Every time I read a few lines, I had to stop, pant, and take a deep breath. The line "I am not a material for diversity" breaks my heart no matter how many times I read it. I am overwhelmed by her complete lack of understanding.

This book was written by seventeen people who tore themselves apart. We call for the publication of writers who live as men/men.

* * * * * * * *

(Redirects to Yahoo! Shopping)

DAIKANYAMA TSUTAYA BOOKS Literature Concierge

Michiko Mamuro

【profile】

"The original charismatic bookseller" who recommends books on various media such as radio and TV. Has serials in magazines such as "Precious" and "Fino". Active as a book critic, his paperback reviews include "The Pale Horse" (Agatha Christie/Hayakawa Christie Bunko), "Motherhood" (Minato Kanae/Shincho Bunko), "The Snake Moon" (Sakuragi Shino/Futaba Bunko), and "Staph" (Michio Shusuke/Bunshun Bunko).